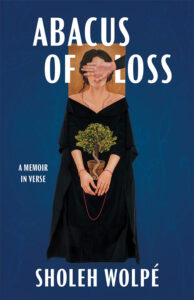

Abacus of Loss, A Memoir in Verse by Sholeh Wolpé

University of Arkansas Press 2022

ISBN 9781682261989

The Abacus of Loss by Sholeh Wolpé is a vivid memoir in verse that unpacks individual memories in a series of thematic strings—the wires of the abacus—each with a different number of beads, from three to thirteen. Their enumeration has a compound emotional effect on the reader and shows how the malleability of time influences memories as they expand and contract, lengthy and detailed discourses, or short, punchy bursts of emotion. Yet every memory counts, every memory adds to the layers of loss that shape life. At times, the narrator’s perspective and her evocative lyricism together with the counting and repetition remind the reader of prayer beads, especially when they include pleas and entreaties.

Wolpé evokes the struggles of living a life of in-betweenness by choosing to combine numbers in Arabic with English letters in the chapter names, which in turn represent the rows of the abacus. Each chapter explores loss from a different angle, both literal and metaphoric. The first piece, for example, presents repeated Persian words fading into the bottom of the page, capturing the multitudes of loss—of language, home, heritage, and even of self.

“that we choose the color

of our loss, like a blue

sash draped across

mourners’ black.”

Language is both a vehicle of communication and a representation of her uprootedness,“my mother tongue ripped blue from my throat.” It distinguishes her otherness: “I wish I could iron my tongue, crease it sharp so I could belong,” not only in her youth but even later; it continues to remind her how she is perceived in America, “Sitting with three open books black with the meandering calligraphy of a ‘terrorist language’ at an American airport is a terrible idea.”

By exploring loss, exile becomes a cornerstone of the memoir, vividly depicted: “Exile is a suitcase with a broken strap.” The loss is perpetual and alters not just the narrator, her family, her neighbors, her world but her whole being, even her subconscious, “I lose the way to my next dream. Like a candle in a paper boat Daddy offers me to the sea.” The short, forceful sentences capture the displacement of values, “It’s exhausting to protect a girl in a place like America”; the dissolution of professional identities, “Dr. so-and-so is now a dishwasher at a diner in DC”; and the aching vacuum of place.

“Refugees trail the narrow roads

like sheep wandering edges

of hallucination.”

There’s a universality of experience for any immigrant who has experienced the turmoil of reconciling the culture at home with the lived external one; the culture dreamt and imagined with the reality of life in America. In a verse entitled “Dear America” Wolpé writes

“I thought you were azure, America,

And orange, sky and poppies.”

The disappointment of America ends up becoming a lifelong search for home, in both the obvious and the unexpected, “I look for home under every rock, inside every shirt, between pistachio shells, even in the smoky cloud rising from kebabs cooking over hot coals.”

We embark with the narrator on her relentless interrogation of the meaning of home: “I left home at thirteen.” And whether it’s the loss of the childhood home, “There is my childhood house becoming smoke.” Is it where we keep our things? “Is home my ghost? / Does it wear my underwear / Folded neatly in the antique chest / of drawers I bought twenty years ago?” Is it the homeland, where we are born? “Home was the Caspian Sea, the busy bazaars, the aroma of kebab and rice, Friday lunches, picnics by mountain streams.”

We are submerged in the narrator’s world, following her from school, “Mama talks as if she’s swallowed the school principal’s loudspeaker,” to marriage, “To escape Daddy’s rules, I get married. He is relieved,” then motherhood — “So I have children. They teach me everything except the meaning of home” and divorce — “I divorce and marry again.” She explores the meaning of identity: “I am sitting where I must not, a blasphemy in red, — the wild-horse woman I strain to keep under check,” discovers sex, “the only way to have sex is to get married,” and finds out what it means to be a woman as she transforms from innocent, “I am so naïve,” to sensual “my last lover left behind.”

She explores the suffocation of the male gaze:

“I close my eyes, pretend the man is a cockroach, but his stare laser-burns my nipples, sets fire to the twin cities under this thin purple blouse.”

By defining the essence of beauty, “Beauty opens its eyes and greets us with its sky,” and rejecting the need to become what she is not, “My skin isn’t dark enough. (…) My hair doesn’t curl tight nor does it drop straight like a waterfall.” She examines acts of transgression on the body in “Please Stop” in Chapter Four, “The day a lover shoved me hard against the bedroom wall and bruised my wrists, I said, please, stop.” The illustration at the beginning of the chapter is of a bird attempting to escape a boiling kettle. In the poem in the last bead, we hear how the kettle begins to “whimper like an injured bird,” and understand that “that whimper was yours all along.”

Chapter Six is one of the longest chapters. Entitled “Pink” with twelve beads, it lays out the narrator’s feelings of anger and betrayal over the forced abortion that her best friend undergoes, the “girl who was once the jewel of Tehran,” their “friendship like a two-paper origami.” She expresses her disdain for her friend’s Persian lover, “They were once in love or lust,” and describes how “his leather shoes suction the linoleum floor,” and how he brought her friend, “tuberoses wrapped in golden cellophane.” His insistence that he loved her friend faces the narrator’s unvocalized contempt coupled with her friend’s agony:

“How is she? he asks. I shrug.

He drops his head, shakes it east to west, west to east.

I do love her, he says.

His eyes are the color of burnt toast.

I rub the pain between my eyebrows, tell him, She doesn’t want to see you. He nods, turns to leave then stops. Tell her I’m sorry. For this. For everything.

I want to say, Tell her yourself, jellyfish. But my tongue is suddenly stone.”

Her friend’s relationship with God contrasts with her own, “I tell Mama I am leaving religion and its foggy tales. She points at the wall of books in my room, says, It’s their fault.” She explores the tension of religion throughout the memoir yet dives deep in Chapter Seven, entitled “Faith,” where Bead 8 entwines translations of Rumi poems with the narrator’s own words, “God weeps behind the mask tattooed on its face.”

The push and pull between the narrator’s different family relationships add layers of strain and complication. The complexity of love, the tensions, the regrets all intermingle with memories, so that by the end, the narrator feels a sense of gratitude for all the moments she has lived, even if painful and replete with suffering. She attends the “Circus in Tehran with tigers, elephants, horses, and shirtless men in glittering tights” with her grandfather; watches while her “grandmother cooks and gives plenty of advice”; rolls her eyes when her “aunt calls on the phone and monologues for hours”; recoils when her “brother kicked with his words, called me whore because I live with a man out of wedlock”; and despairs, “Daddy says he’ll never speak to me again.”

She is overwhelmed, “I tell Mama, Look, I’m bathed in light. She says, No, child, it’s the Beloved leaving your soul.” The intensity of emotions felt for each family member is how the narrator explores devotion, sacrifice, anguish, and the ability to continue to love those who inflict pain on us, “The house is corpses of women, cooking meal after meal,” yet these “Women sing absence like opera.”

Certain images recur throughout the memoir and linger with the reader. Pistachios are associated with different men, both close, “Daddy empties his plate of pistachio shells into the trash,” and distant, “I’ve never had a pistachio, says the bartender. (…) I crack the shell like a vow.” The color blue evokes the promise of America but also unrequited love and lies, “Where blue is light’s repeating lie.” Red is lust, “He runs his broom to and fro, moving dust closer and closer to my ridiculously high-heeled red shoes, then stops”; sin, “There are pieces still clinging to her womb like strands of red algae”; and the powerful refusal to live within limitations, “the color that refuses.”

I never wanted this memoir to end, each time I reread the words, they felt more heart wrenching, laying bare what is unexplainable with evocative, visceral lyricism:

“Darkness bends over itself to devour

What it will not hold”

I am immersed in the narrator’s world, unwilling to leave. I listen to her conversations with her aging parents:

“The baritone-roar of hairdryer stops like the engine of a plane that has just arrived. Mama descends the narrow stairs like a queen in a fluffy blue robe. She says, What are you two whispering about?

It’s not a question. She doesn’t wait for an answer because she imagines there is nothing about Daddy she does not know. Not after fifty-five years. She shuffles in her slippers into the kitchen to make the evening’s meal of rice and stew.

Mama is frying onions now. The sweet smell permeates the room with nostalgia. She hums to a tune in her head and I think: Mistakes are the sinews that hold our bones.”

The last wire of the abacus has three beads; the first talks of exile, “Moon drove us into dizzy exile, Language became a desert with no name,” the second, of acceptance that life goes on as the narrator attends a funeral with her parents “in the same cemetery where our parents have bought their burial plots, (…) Mama and Daddy practicing their own absence,” and the final one, of gratitude “Listen, nothing’s too small for gratitude.” By the end, gratitude is my dominating emotion, gratitude for Sholeh Wolpé’s memoir, for every thought-provoking word, for her raw honesty, for how she unpacks the complexities of exile, home, family, love, and everything in between. I am extremely grateful, thank you.

Review for The Art of Remembrance in “Abacus of Loss” appeared in The Markaz Review